Fonte:

www.timesofisrael.com

Autore:

Matt Lebovic

During WWII, Dr. Seuss tried to slay anti-Semitism, but also promoted racism

With late author’s estate declining to republish six of Theodore Geisel’s books, we present a look at Dr. Seuss’s foundational years as US Air Force propogandist extraordinaire

Lost in the fracas about beloved children’s author Dr. Seuss’s racially offensive books is that the iconic writer and illustrator launched his career by denouncing German expansionism and going after racists and anti-Semites at home.

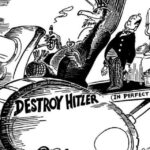

For Theodore Seuss Geisel — better known as Dr. Seuss — the lead-up to World War II provided unparalleled creative opportunities. At New York’s liberal-leaning PM daily newspaper, Geisel created more than 400 cartoons to help prod Americans into a war that most people did not desire.

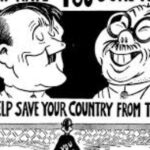

“His cartoons attacked reactionaries and isolationists such as Charles Lindbergh, and in a few instances he ridiculed anti-Semitism in America,” said Rafael Medoff, historian and coauthor of the book “Cartoonists Against the Holocaust.”

“Many of Seuss’s cartoons mocked Hitler and the Nazis, but only one of them addressed the plight of the Jews in Europe,” said Medoff in an interview with The Times of Israel. “It was one of the most graphic cartoon portrayals of the Holocaust at the time, showing Jewish corpses hanging from trees in Nazi-occupied France,” said Medoff.

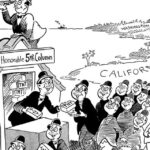

While Geisel’s cartoons sometimes depicted the folly of racism, he also penned bigoted cartoons of Japanese American citizens and Japan. In one notorious 1942 cartoon, Japanese Americans were seen in line as a “fifth column” with each of them being handed a block of dynamite.

“[That cartoon supporting] President Roosevelt’s mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans depicted them as slant-eyed fifth columnists and terrorists,” said Medoff, who is also director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies in Washington, DC.

“It was a reprehensible defense of a reprehensible presidential policy,” said Medoff about the anti-Japanese cartoon. “Sadly, this appears to be typical of American political cartoonists at the time; in my ongoing research, I have not yet found any cartoons opposing FDR’s mass detention policy,” said the historian.

‘Your Job in Germany’

For Geisel and artists, America’s entry into the war provided a host of creative opportunities.

As chief editorial cartoonist at “PM” daily newspaper from 1941 through 1943, Geisel’s 400 cartoons urged Americans to go to war against the Axis. He depicted the “America First” movement as an “Isolationist Ostrich” while condemning racism and anti-Semitism.

As a third-generation American whose four grandparents were born in Germany, Geisel had a keen interest in European affairs. During the interwar years, he traveled there and formed opinions on fascism through first-hand encounters.

Based on Geisel’s success at PM newspaper, the US Air Force adroitly snatched him up for the war effort. Geisel created a series of home-front posters urging Americans to enlist and buy bonds, but it was for enlisted soldiers that his most memorable artistry was directed.

In 1944, Geisel helped make “Your Job in Germany,” a documentary to instruct soldiers on how to behave as occupiers. “The Nazi party may be gone, but Nazi thinking, Nazi training and Nazi trickery remains,” warned the narrator. “The German lust for conquest is not dead.”

During the short film, Germany’s three failed wars since 1870 were reviewed, alongside a warning for soldiers not to believe that Germans want peace.

“Every German is a potential source of trouble,” said the narrator, pointing to the “vicious cycle of war, phony peace, and war again,” with the sound of explosions in the background.

Geisel also worked with Hollywood legend Frank Capra on the “Why We Fight” series, and he co-created 30 episodes of the animated “Private Snafu.” In that animated series, soldiers were taught about the dangers of — for example — fraternizing with Germans and malaria.

In early 1945, Geisel set off to Europe to screen new propaganda films for the generals. While there, he was caught behind enemy lines during the Battle of the Bulge and extracted by British soldiers. The upshot: Ike told Geisel he approved of the latest propaganda film.

After Hitler’s defeat, Geisel worked on the film “Know Your Enemy — Japan,” to educate soldiers about the coming occupation of that nation. On the day the film started to be screened for soldiers, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, and General MacArthur ordered the film withdrawn.

For his service during three years in the military, Geisel was awarded the “Legion of Merit.” In later decades, his books would include examples of fascism, persecution, and discrimination, part of Geisel’s attempt to give children a moral education.

In Medoff’s opinion, there are some Dr. Seuss books that could benefit from a publisher’s message upon opening the cover. Specifically, he pointed to “Yertle the Turtle,” calling the story “a thinly-disguised parable about the dangers of following aspiring fascist leaders.”

In “Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories,” the so-called “King of the Pond” Yertle stands on the backs of other turtles in order to reach higher than the moon. Eventually, the turtle at the bottom lets out a belch that frees the others and dislodges Yertle from his throne.

“That book, too, can be an excellent teaching tool,” said Medoff.

In Medoff’s assessment, the racial stereotypes identified in Geisel’s other books and cartoons should be put into context by publishers.

“The minorities who were portrayed in those Seuss books in offensive ways are understandably upset — just as many Jews have protested in recent years when certain political cartoonists have used anti-Semitic imagery in portraying Jews or Israel,” said Medoff.

However, to turn this into a learning moment, he said, a publisher can include a note to parents and teachers “encouraging them to use the imagery in the book as a way of explaining what’s wrong with those stereotypes,” said Medoff.